The Real Hidden Courts of New York

New Yorkers complain about Central Park crowding. But a subway-ride away...

Aug 30, 2024

The West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills, once the site of the U.S. Open, on a warm October evening.

Every year about this time — when U.S. Open fever hits New York — the New Yorker republishes its notable Shouts & Murmurs from 2018, “The U.S. Open, Played on New York City Public Courts,” and invariably, the New York Times comes out with a service journalism story about the state of New York City public courts.

Well, the state of the tennis courts (not pickleball or Padel) — both public and private — has not changed all that much since possibly 1970? Every April, the city opens up its public courts to about 2,000 people willing to pay $100 for a permit to play on about 500 courts city-wide reserved with old-school, pen-and-paper sign-up sheets, manned by court attendees and entrusted the tennis player « honor system ». Those who want to hit at Central Park or Prospect Park or some others, can wait for a spot to open up on a 15-year-old website — and pay an extra $15 for the privilege of reserving online. Sometimes, they can get a court saved for them by an enterprising New Yorker on craigslist. If they want to pay for a club, there are a few on offer, such as the West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills, Queens — a gorgeous, legendary facility with tons of displayed history and panache, not to mention clean locker rooms. But the fact of the matter remains: most New Yorkers cannot afford West Side ($5,000 to join, about $300 per month in fees) or most of the other clubs in town.

Six years ago, theTimes put out a story about the courts of New York City, which included the Central Park Courts, the East River Courts, two court facilities in Brooklyn (McCarren and Fort Greene) as well as the 96th Clay and the Cary Leeds Center. One could usually book a decent pick-up game at the former Brian Watkins Tennis Center on the East River, but that was demolished in 2021 to make way for a hurricane-damage reduction berm put into the works following Hurricane Sandy. Other than that, most of these courts are impossible to reserve, usually booked for the day by 8am. But look a little closer, travel a little farther, and voila! New York tennis opens its chain-link doors to the willing and the desperately wanting.

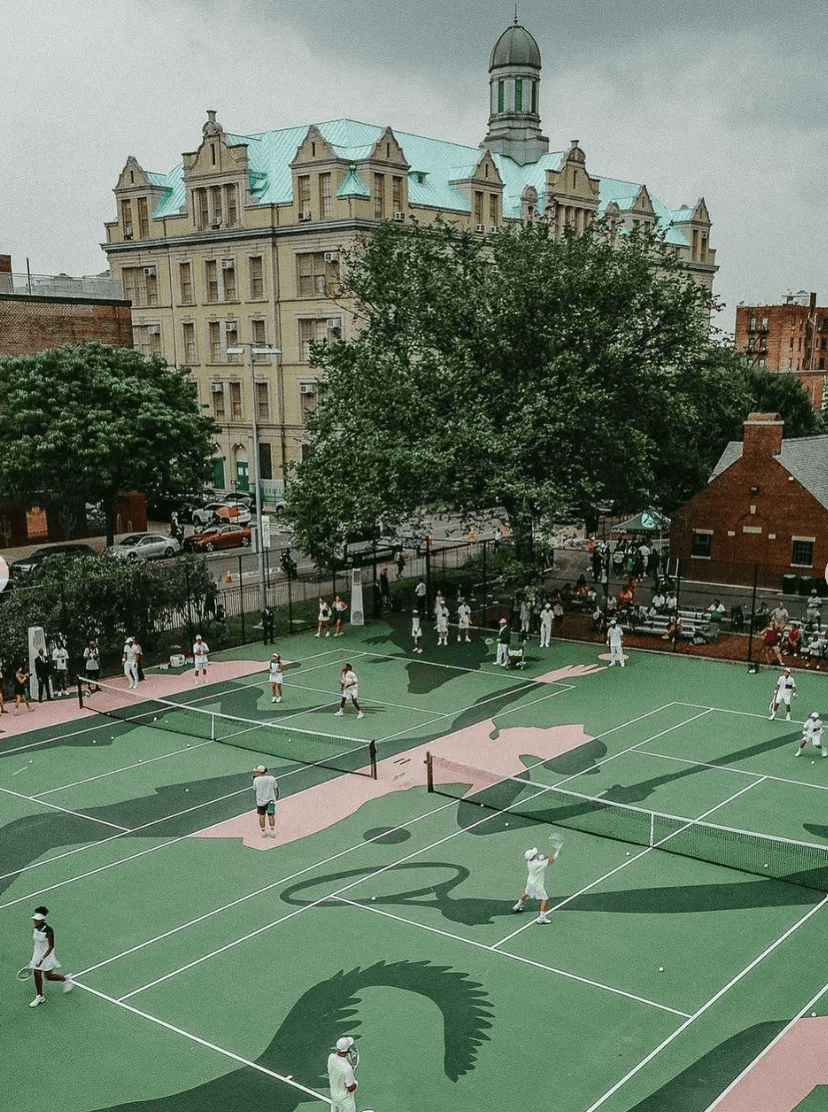

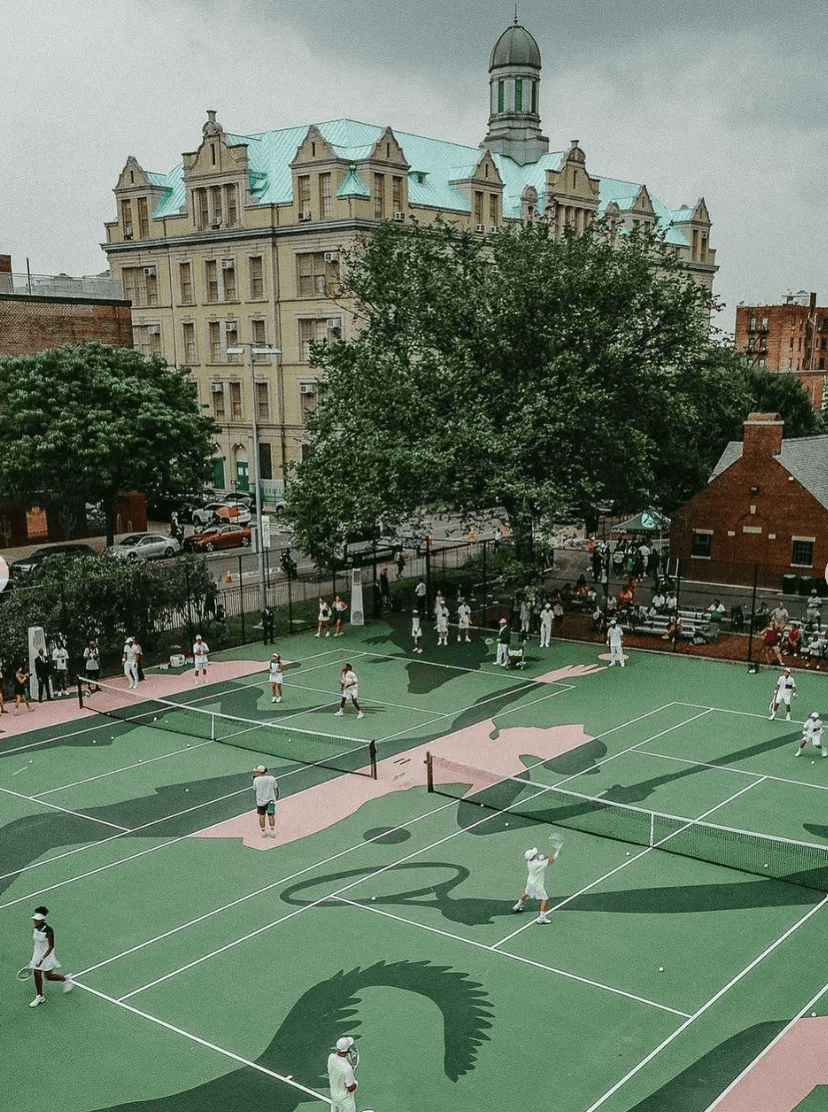

In honor of Lacoste’s 90th anniversary, Venus Williams and the clothing company helped renovate two tennis courts in the Bronx — courts long neglected by the city.

Over in Flushing, Queens, however, Thursday proved a surprising and challenging day for the seeded players and even some of the hometown favorites. To begin with, the biggest upset of the day came when 28-year-old Netherlander Botic Van de Zandschulp (ATP No. 74) bested the younger, faster, yet still Olympic-PTSD-suffering Carlos Alcaraz (ATP No. 3), ending his efforts to claim the U.S. Open trophy for a second year straight. Meanwhile, after a marathon first round match — the longest in Open history — British player Dan Evans (ATP No. 184) demolished his second-round opponent, Argentina's Mariano Navone, in three sets, giving much gratitude to his physio for reviving him. Today in the men’s draw, rivals Francis Tiafoe (ATP No. 20) and Ben Shelton (ATP No. 13) compete on Ashe, while American Taylor Fritz (ATP No. 12) now has a wide-open chance to continue his run if he can overcome Argentinian Francisco Comesana.

In the women’s draw, the bows and the ballerina skirts of unseeded Naomi Osaka (WTA No. 88) exited stage left with a straight-sets 6-3, 7-6 loss to Karolina Muchova (WTA No. 52), who reached the 2023 U.S. Open semifinal. Many of the Americans also remain in the draw with Coco Gauff (WTA No. 3) up against Elina Svitolina (WTA No. 28), Jessica Pegula (WTA No. 6) still alive and well, and up-and-comer — and straight-talker — Emma Navarro (WTA No. 12) playing Ukrainian Marta Kostyuk (WTA No. 19).

But for New York players hit by U.S. Open fever, the following are some courts that keep a regular match within reach.

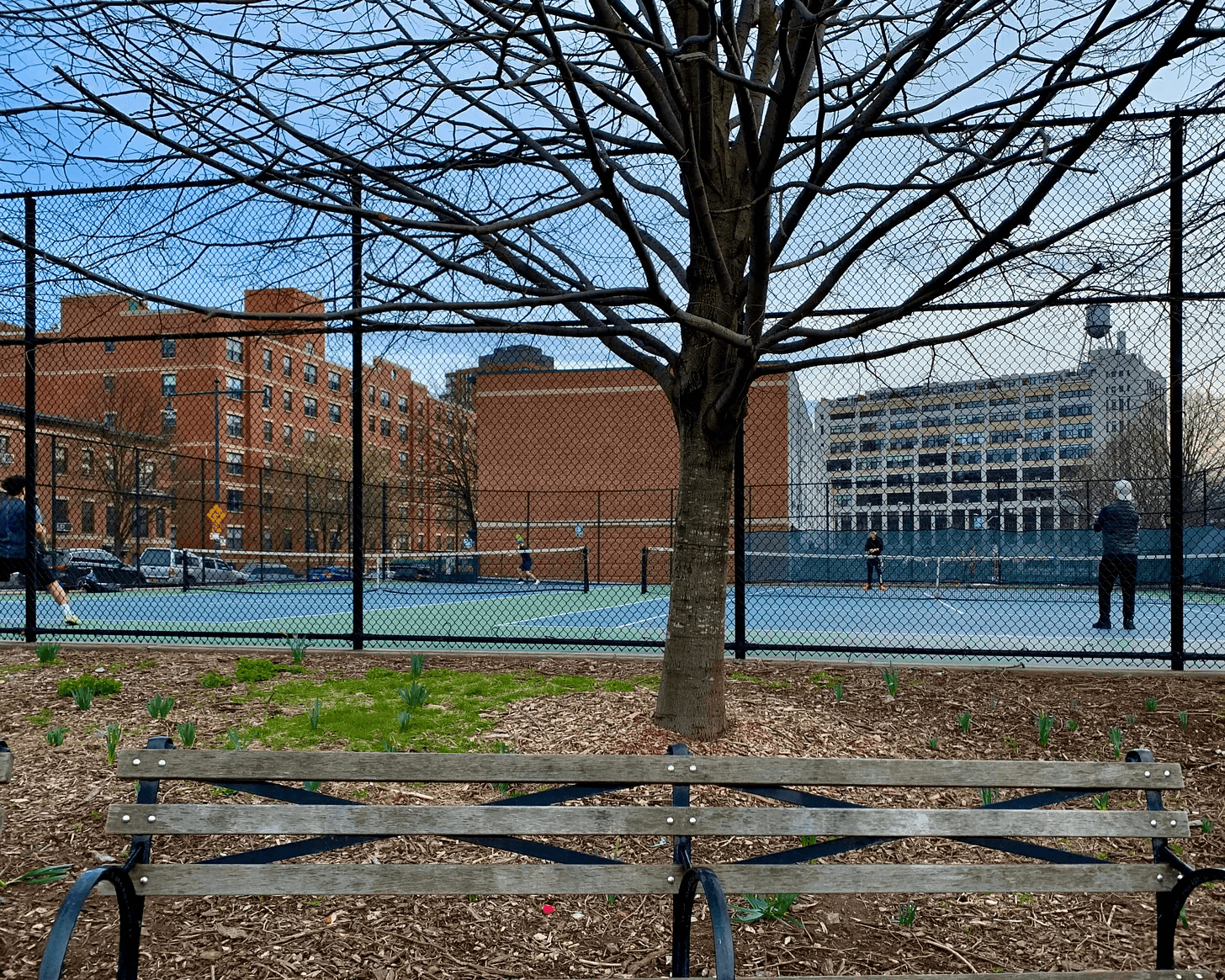

In the middle of Fort Greene sit two sacred courts among locals. Quiet — and even picturesque — the South Oxford Courts are the holy grail of NYC tennis.

South Oxford Park Courts

Nestled among the Atlantic Commons development, a Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) apartment complex, are two hardtop courts, one singles and one doubles, on top of the place where the South Oxford Tennis Club used to stand. Once the only black-owned tennis club in New York City, during its 16-year existence, South Oxford offered free lessons, tournaments and hip-hop events. When the city closed it in 1997 and demolished the clubhouse in 2001, it built the park on the old grounds.

Built on the old South Oxford Tennis Club, the courts now require a sign-up sheet, but that’s about it.

Unlike the other Fort Greene courts, these are also two of the few in Brooklyn where people can get away with playing without a permit. The only problem: coaching. The park does not have an attendant to make sure rogue instructors stay off the courts. South Oxford relies on sign-up sheets allowing players to reserve hour-long sessions — sometimes more, if no one is paying attention in this relatively noiseless, drama-free corner of New York.

Crown Heights’ Lincoln Terrace Tennis Center glows brightly in its urban Brooklyn neighborhood — one of the few places juniors have a summer academy.

The Lincoln Terrace Tennis Center

Lincoln Terrace Park is one of only two New York City parks named for the 16th president, Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) and has long been a haven for the people of Brownsville, Crown Heights and East Flatbush. The 11 courts date back to the 1930s and were reconstructed in 1996 and again in 2014 with a new surface, retaining walls, fencing, benches and lighting.

As early as 1949, Top-50 players were teaching around the neighborhood — about 25 minutes from from Chambers Street on the 3 train. Phil Rubell, a U.S. Postal Worker who played in college, charged $30 per half-hour lesson in the 1950s to supplement his mail carrier salary. Rubell became so popular that the Parks Department built a wooden house adjacent to the courts for him to sell racquets and clothing — and in retirement, his side hustle became his main hustle. Rubell’s son, Steve, who took lessons from his father, went on to captain the team at Syracuse University, but instead of turning pro, opened several restaurants before his most famous venture: Studio 54.

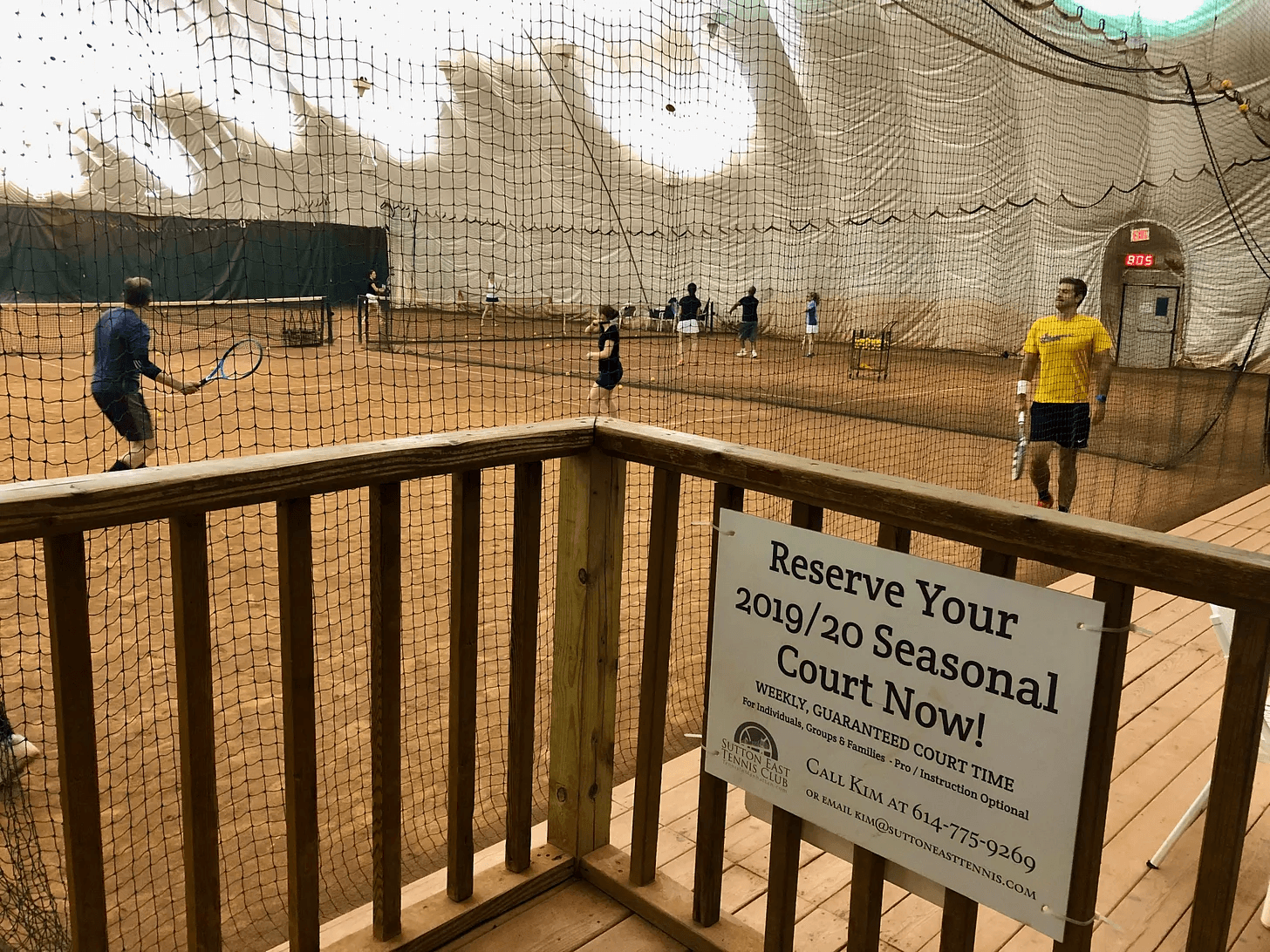

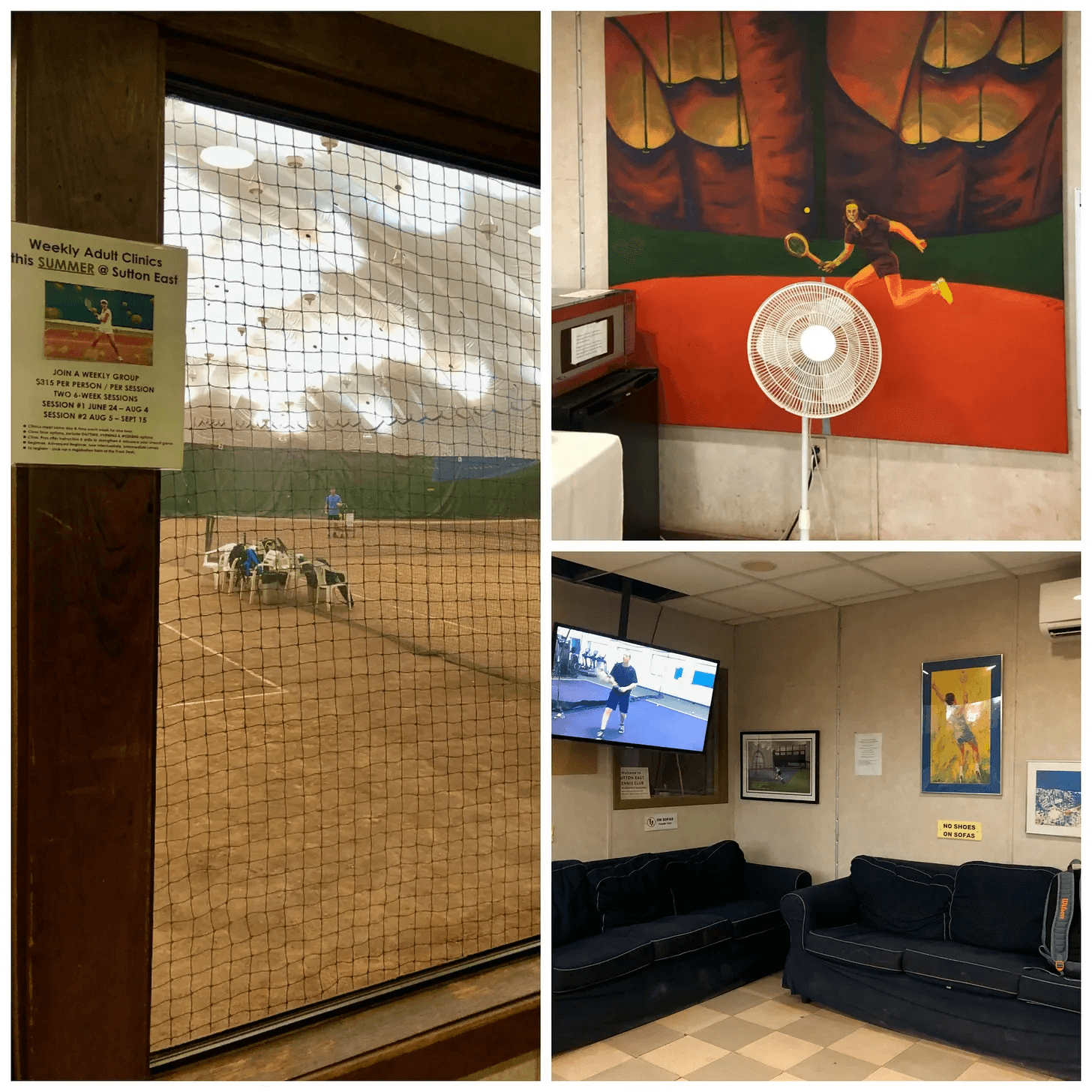

The indoor bubble at Sutton East Tennis Club. Built on park grounds, the group that runs the club now allows reduced rates for Seasonal Park Pass holders.

Sutton East Tennis Club

In mid-2017, the populists of the Upper East Side finally won a battle against the elitists. A spot of rich, red clay courts formerly known as the Queensboro Oval tennis bubble — operated by a group calling itself Tennis in Manhattan through a license agreement with the city — opened to city tennis permit holders, following a rancorous grassroots battle cry. East Siders wanted a multi-sports venue with an ice-skating rink in the winter, but the one-acre tennis facility, under the Queensboro Bridge on the Manhattan side — which once hosted softball players in the summer, tennis players in winter — went all-season on June 16, 2017, handing over six of the club’s eight courts to city tennis permits at no extra cost. Normally, the club charges from $80 to $225 per court per hour during peak off-season times.

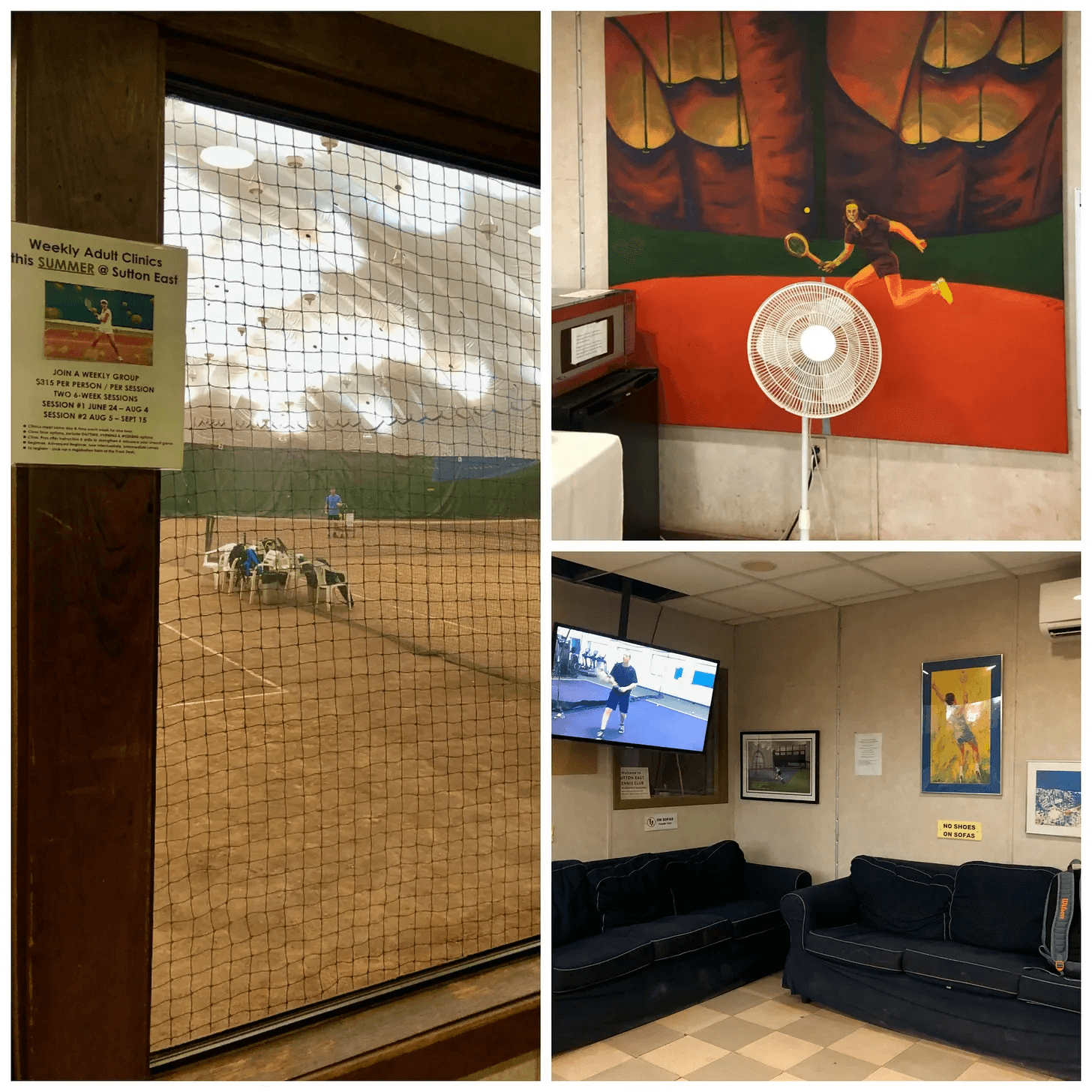

The lounge at Sutton East Tennis Club. Half-indoor, half patio, it’s one of the most unusual waiting areas in Manhattan.

Tony Scolnick, the proprietor of Tennis in Manhattan, which runs the Vanderbilt Club at Grand Central Station as well as the Yorkville Tennis Club, opened Sutton East in 1979. He currently pays a $2 million per year lease on the land to the city. When the neighborhood ballplayers gathered 1,000 signatures to convert the grounds back to a city park, Scolnick, a former Athletic Director for Hunter College and player at Springfield College in Massachusetts, fought back with 3,000 signatures from users of Sutton East. “People will be thrilled because when it rains in the summer they can't play outdoors,” he told the former news site DNA.info in 2017. “We believe thousands of people who play at our facility, if they don't have a permit, will go and get one. We are very happy to maintain the courts.”

An after-school program of New York Junior Tennis and Learning (NYJTL), which has the courts weekday afternoons. Evenings and weekends, courts cost a pittance.

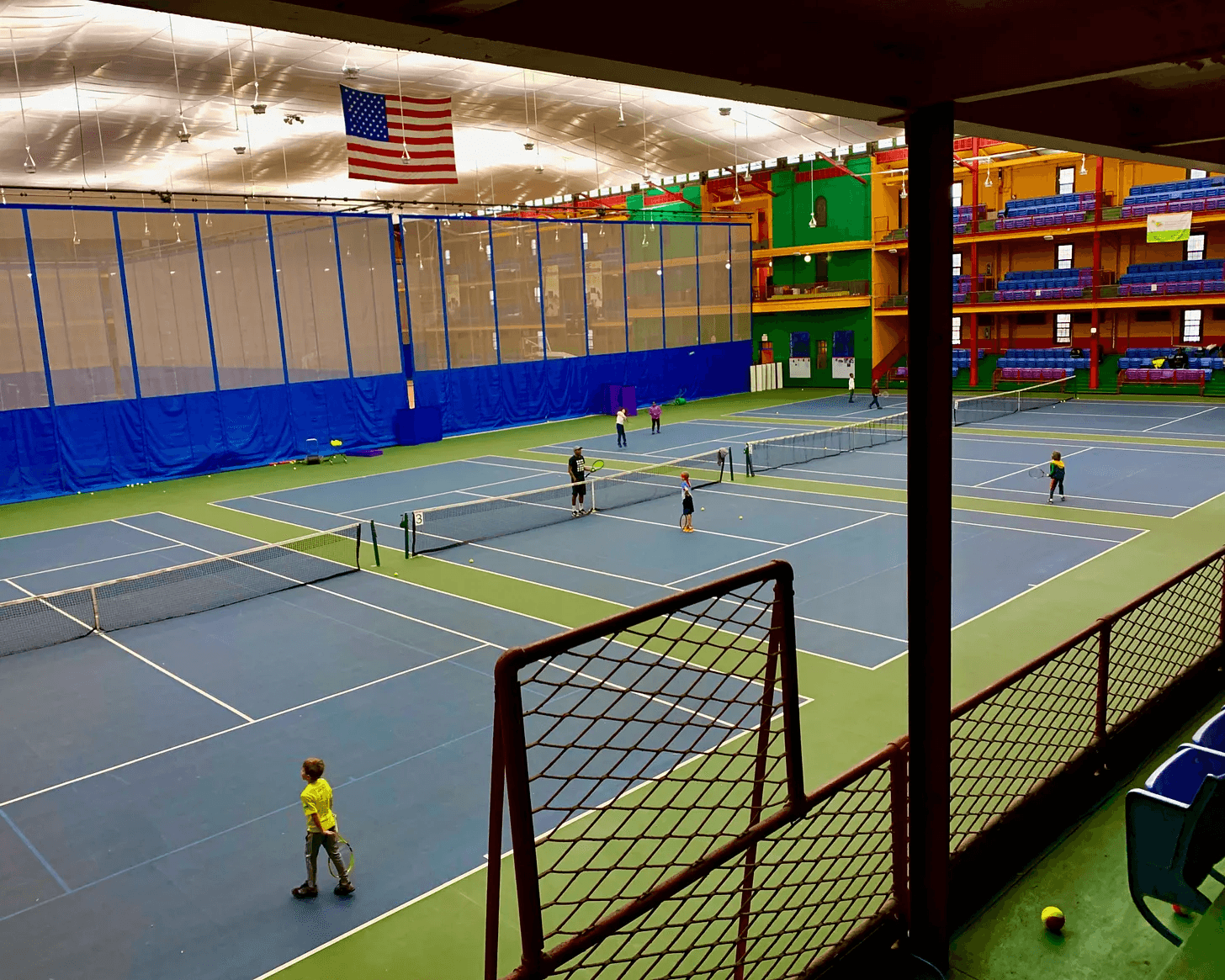

The Harlem Armory

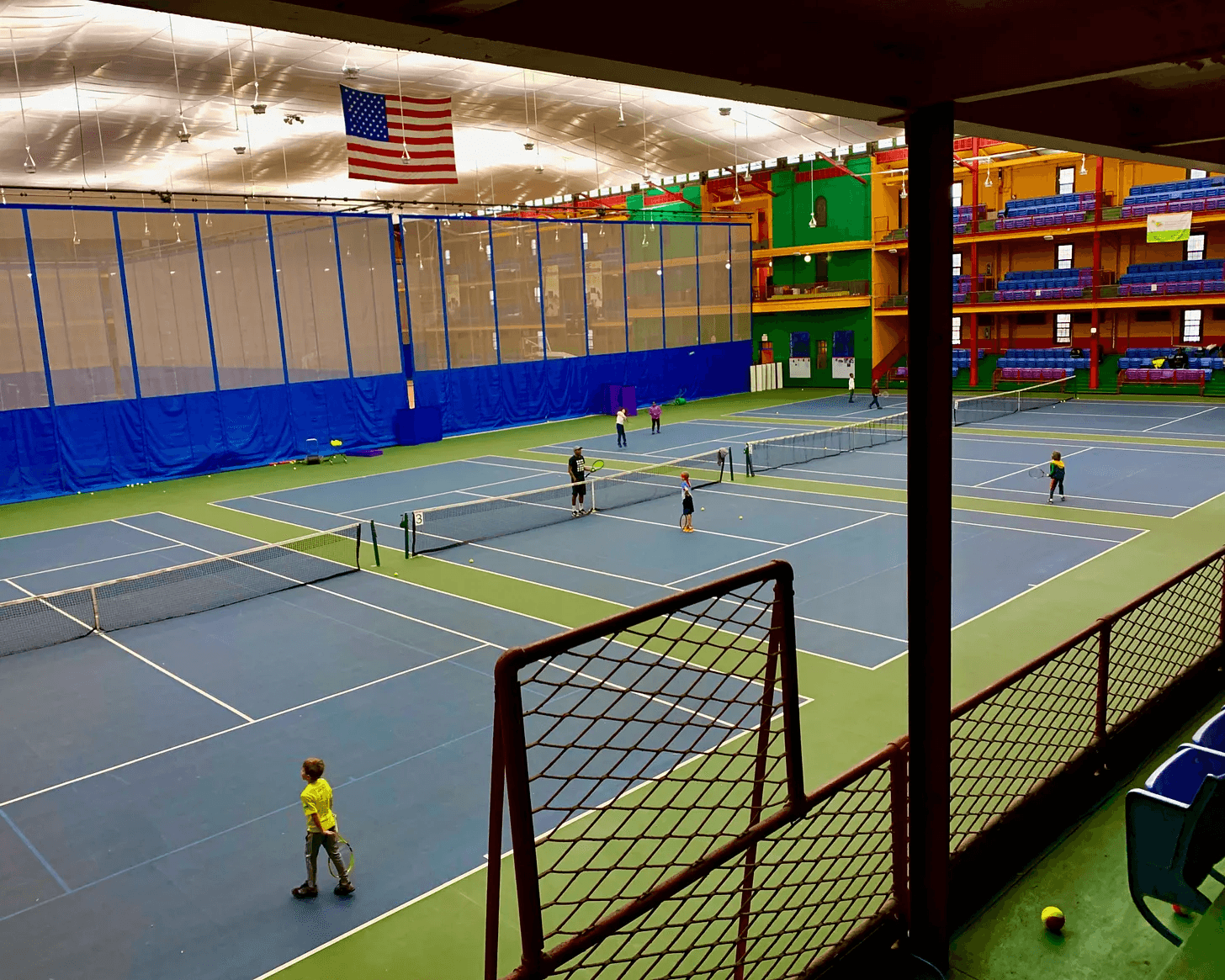

Located at the Armory building at 143rd Street and Fifth Avenue — the former home of the 369th Regiment “Harlem Hell Fighters” — the Harlem Armory Tennis Center runs eight indoor courts on the medieval-inspired drill shed built in 1921 for once training the New York’s first black National Guard regiment. After the war, Nick's Indoor Tennis took over the facility, followed by Bill's Indoor Tennis, which then became the Harlem Tennis Center (HTC). During the afternoons, the Harlem Junior Tennis and Education Program (HJTEP), runs programs for local children. But during mornings, nights and weekends, courts are available at below-market rates.

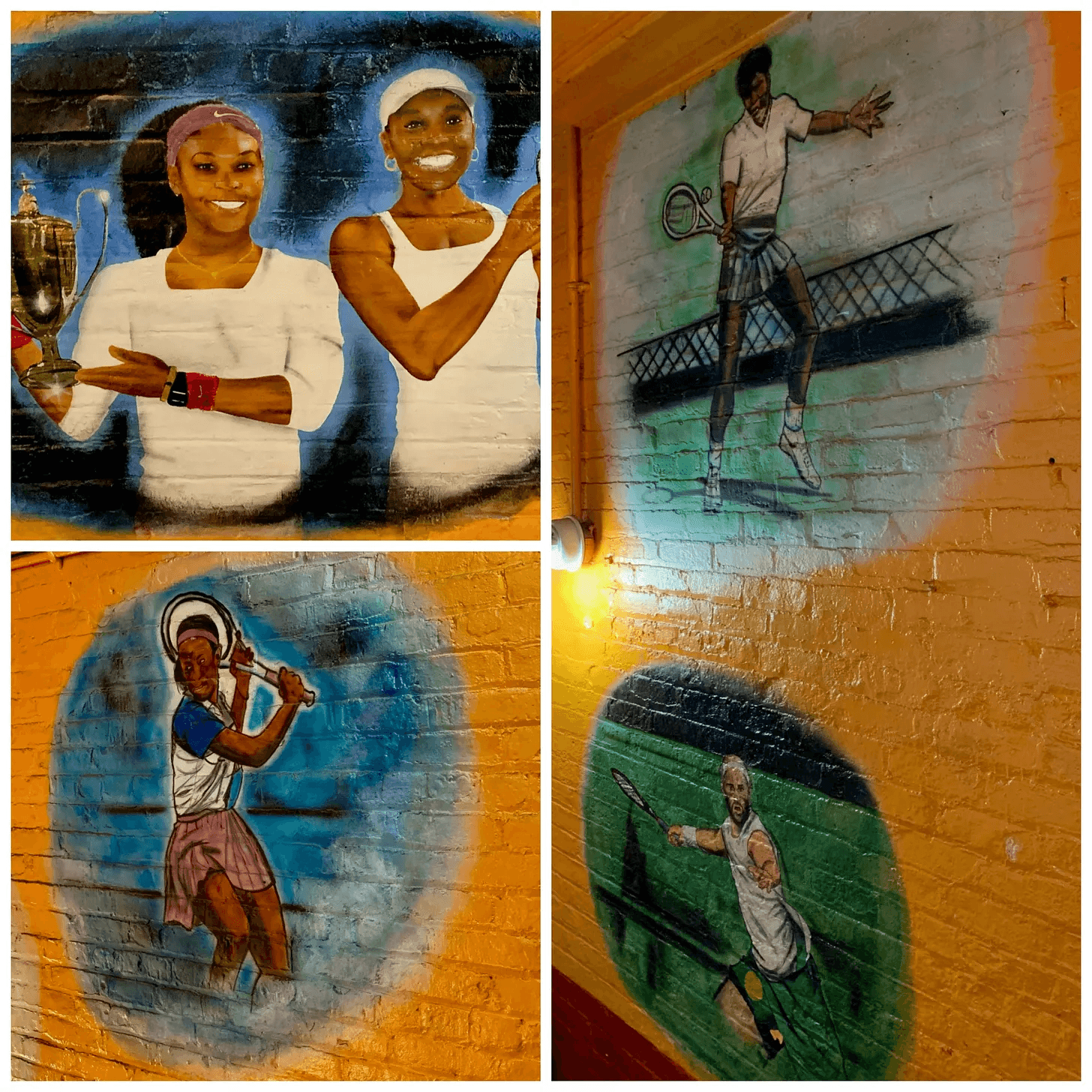

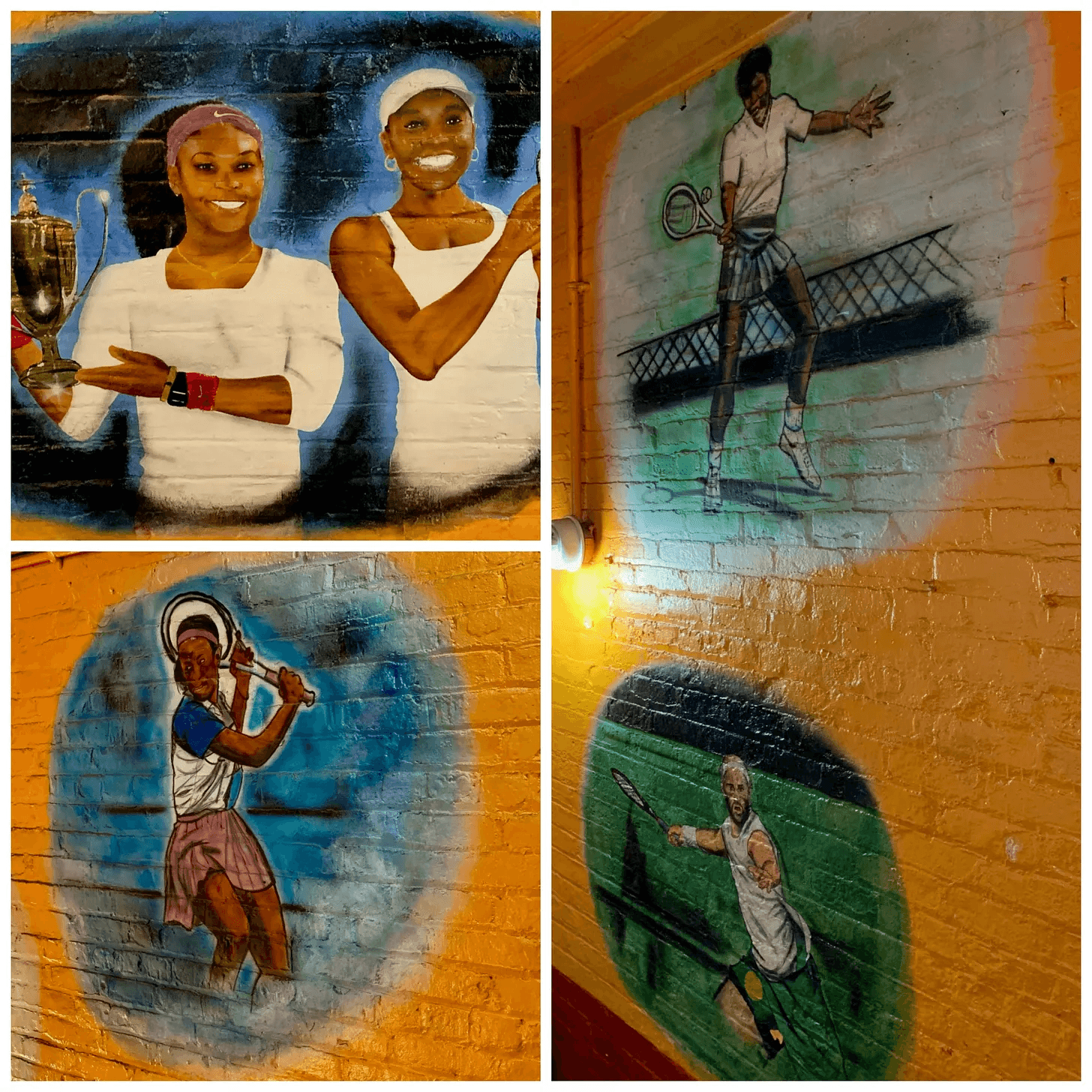

Graffiti portraits of some of the great Black tennis players of the modern era line the stairs leading up to the court-office at the Harlem Armory Tennis Center.

The armory, which also has a nice art-deco wing, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1994. Tennis greats Arthur Ashe and Althea Gibson played at the Armory before getting involved in junior tennis — Gibson in Newark and Ashe with the New York Junior Tennis and Learning (NYJTL) program. Under the city bankruptcy tenure of Mayor Ed Koch, half of the courts were used as homeless shelter, but Mayor David Dinkins — an avid tennis lover and player — turned over the courts to HJTEP in the early 1990s.

The courts at the Frederick Johnson playground light up around 6pm every day, even in the winter.

Frederick Johnson Park

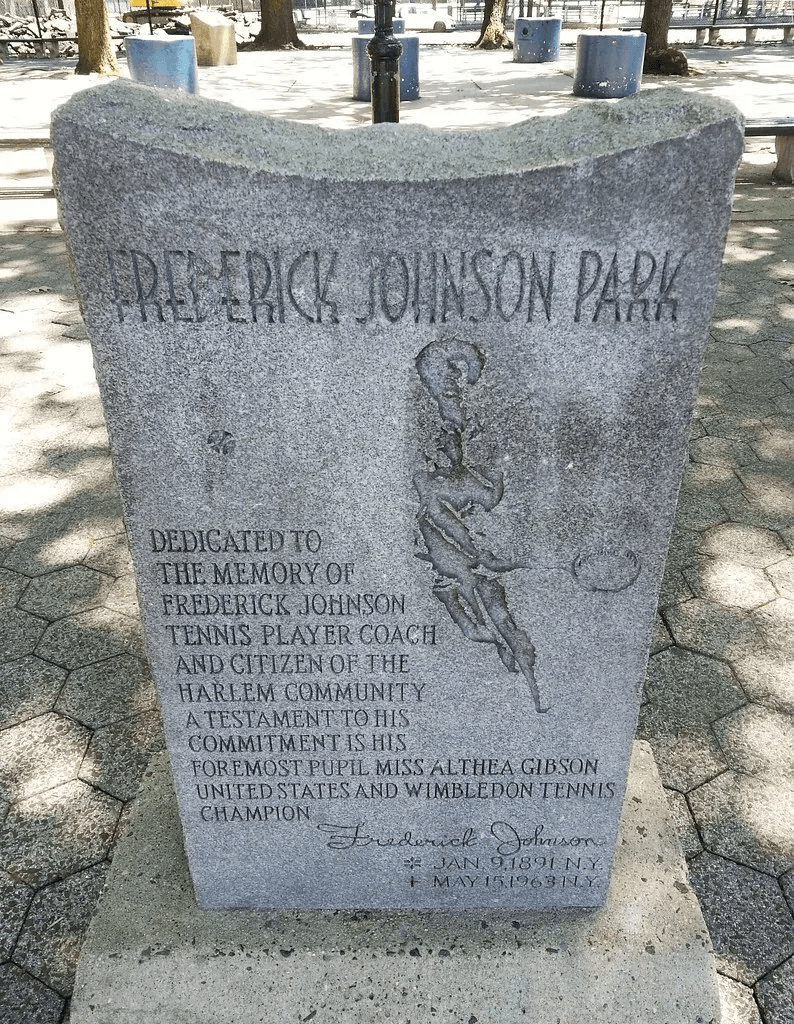

Possibly one of the least-known tennis jewels of Manhattan, the recently restored Frederick Johnson Playground offers eight courts in Harlem, open from April through November — with lights! Once affectionately known as “the Jungle”, according to the Times, these courts were also once a mecca for top African-American players. Frederick Johnson, the park’s namesake, coached Althea Gibson there — with one arm.

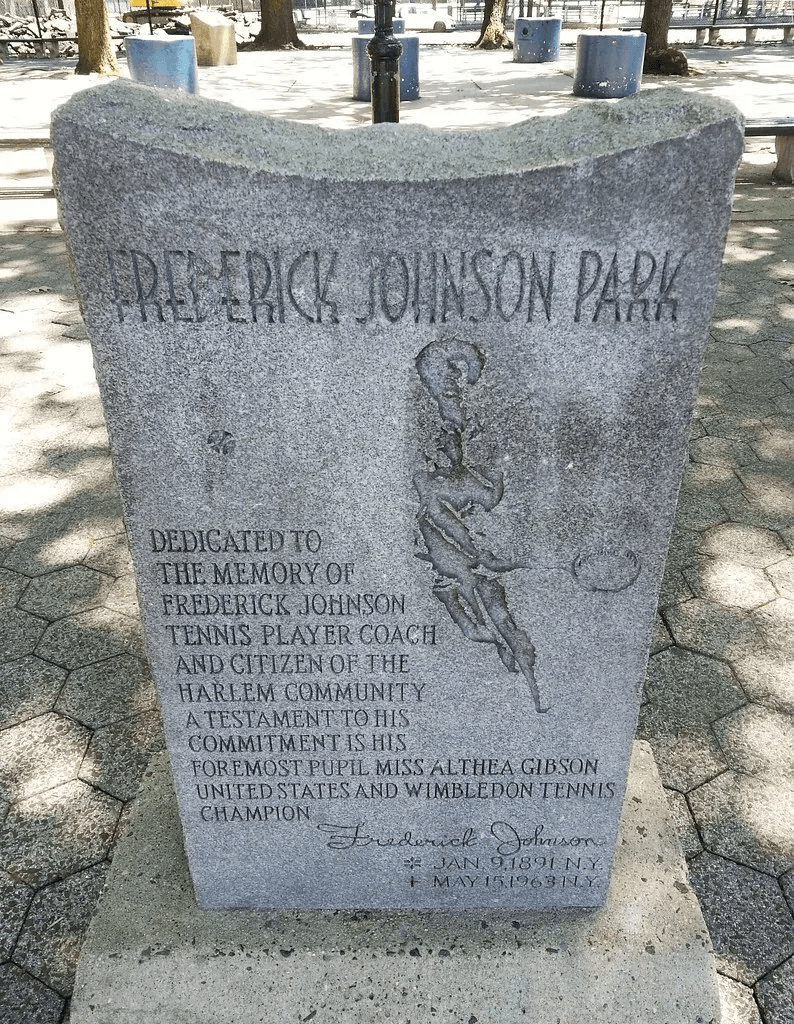

A monument to the Park’s namesake, who coached Althea Gibson as a young girl.

In 2010, former mayor and tennis enthusiast, David Dinkins, helped form the David Dinkins Tennis Club — a free family program on summer weekends. Dinkins was also instrumental in installing lights at Frederick Johnson when he served as Manhattan borough president in 1986. But other than that programming, the city has maintained a mostly hands-off approach to the small slice of New York tennis utopia tucked into a corner of northeast Manhattan.

The West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills, once the site of the U.S. Open, on a warm October evening.

Every year about this time — when U.S. Open fever hits New York — the New Yorker republishes its notable Shouts & Murmurs from 2018, “The U.S. Open, Played on New York City Public Courts,” and invariably, the New York Times comes out with a service journalism story about the state of New York City public courts.

Well, the state of the tennis courts (not pickleball or Padel) — both public and private — has not changed all that much since possibly 1970? Every April, the city opens up its public courts to about 2,000 people willing to pay $100 for a permit to play on about 500 courts city-wide reserved with old-school, pen-and-paper sign-up sheets, manned by court attendees and entrusted the tennis player « honor system ». Those who want to hit at Central Park or Prospect Park or some others, can wait for a spot to open up on a 15-year-old website — and pay an extra $15 for the privilege of reserving online. Sometimes, they can get a court saved for them by an enterprising New Yorker on craigslist. If they want to pay for a club, there are a few on offer, such as the West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills, Queens — a gorgeous, legendary facility with tons of displayed history and panache, not to mention clean locker rooms. But the fact of the matter remains: most New Yorkers cannot afford West Side ($5,000 to join, about $300 per month in fees) or most of the other clubs in town.

Six years ago, theTimes put out a story about the courts of New York City, which included the Central Park Courts, the East River Courts, two court facilities in Brooklyn (McCarren and Fort Greene) as well as the 96th Clay and the Cary Leeds Center. One could usually book a decent pick-up game at the former Brian Watkins Tennis Center on the East River, but that was demolished in 2021 to make way for a hurricane-damage reduction berm put into the works following Hurricane Sandy. Other than that, most of these courts are impossible to reserve, usually booked for the day by 8am. But look a little closer, travel a little farther, and voila! New York tennis opens its chain-link doors to the willing and the desperately wanting.

In honor of Lacoste’s 90th anniversary, Venus Williams and the clothing company helped renovate two tennis courts in the Bronx — courts long neglected by the city.

Over in Flushing, Queens, however, Thursday proved a surprising and challenging day for the seeded players and even some of the hometown favorites. To begin with, the biggest upset of the day came when 28-year-old Netherlander Botic Van de Zandschulp (ATP No. 74) bested the younger, faster, yet still Olympic-PTSD-suffering Carlos Alcaraz (ATP No. 3), ending his efforts to claim the U.S. Open trophy for a second year straight. Meanwhile, after a marathon first round match — the longest in Open history — British player Dan Evans (ATP No. 184) demolished his second-round opponent, Argentina's Mariano Navone, in three sets, giving much gratitude to his physio for reviving him. Today in the men’s draw, rivals Francis Tiafoe (ATP No. 20) and Ben Shelton (ATP No. 13) compete on Ashe, while American Taylor Fritz (ATP No. 12) now has a wide-open chance to continue his run if he can overcome Argentinian Francisco Comesana.

In the women’s draw, the bows and the ballerina skirts of unseeded Naomi Osaka (WTA No. 88) exited stage left with a straight-sets 6-3, 7-6 loss to Karolina Muchova (WTA No. 52), who reached the 2023 U.S. Open semifinal. Many of the Americans also remain in the draw with Coco Gauff (WTA No. 3) up against Elina Svitolina (WTA No. 28), Jessica Pegula (WTA No. 6) still alive and well, and up-and-comer — and straight-talker — Emma Navarro (WTA No. 12) playing Ukrainian Marta Kostyuk (WTA No. 19).

But for New York players hit by U.S. Open fever, the following are some courts that keep a regular match within reach.

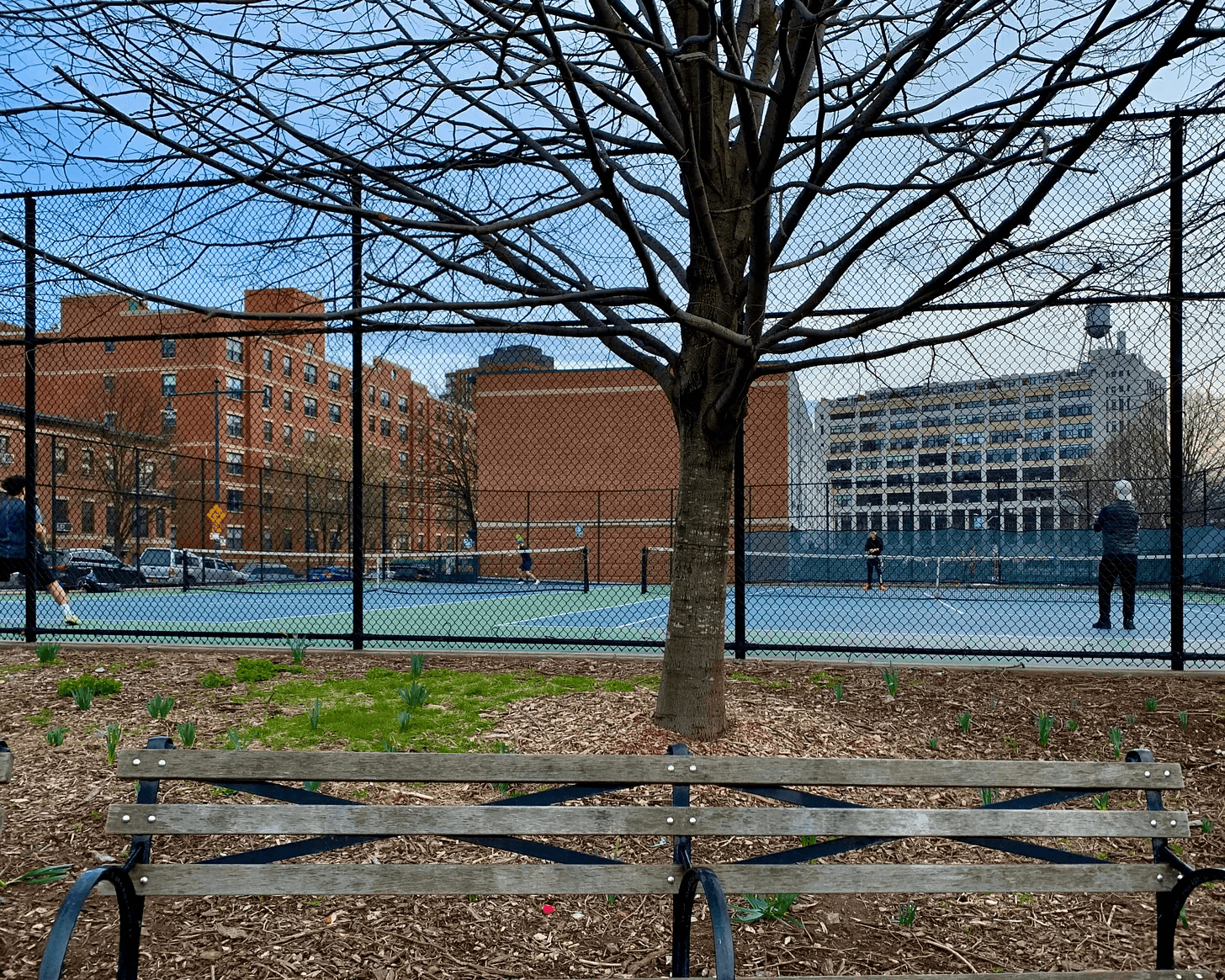

In the middle of Fort Greene sit two sacred courts among locals. Quiet — and even picturesque — the South Oxford Courts are the holy grail of NYC tennis.

South Oxford Park Courts

Nestled among the Atlantic Commons development, a Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) apartment complex, are two hardtop courts, one singles and one doubles, on top of the place where the South Oxford Tennis Club used to stand. Once the only black-owned tennis club in New York City, during its 16-year existence, South Oxford offered free lessons, tournaments and hip-hop events. When the city closed it in 1997 and demolished the clubhouse in 2001, it built the park on the old grounds.

Built on the old South Oxford Tennis Club, the courts now require a sign-up sheet, but that’s about it.

Unlike the other Fort Greene courts, these are also two of the few in Brooklyn where people can get away with playing without a permit. The only problem: coaching. The park does not have an attendant to make sure rogue instructors stay off the courts. South Oxford relies on sign-up sheets allowing players to reserve hour-long sessions — sometimes more, if no one is paying attention in this relatively noiseless, drama-free corner of New York.

Crown Heights’ Lincoln Terrace Tennis Center glows brightly in its urban Brooklyn neighborhood — one of the few places juniors have a summer academy.

The Lincoln Terrace Tennis Center

Lincoln Terrace Park is one of only two New York City parks named for the 16th president, Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) and has long been a haven for the people of Brownsville, Crown Heights and East Flatbush. The 11 courts date back to the 1930s and were reconstructed in 1996 and again in 2014 with a new surface, retaining walls, fencing, benches and lighting.

As early as 1949, Top-50 players were teaching around the neighborhood — about 25 minutes from from Chambers Street on the 3 train. Phil Rubell, a U.S. Postal Worker who played in college, charged $30 per half-hour lesson in the 1950s to supplement his mail carrier salary. Rubell became so popular that the Parks Department built a wooden house adjacent to the courts for him to sell racquets and clothing — and in retirement, his side hustle became his main hustle. Rubell’s son, Steve, who took lessons from his father, went on to captain the team at Syracuse University, but instead of turning pro, opened several restaurants before his most famous venture: Studio 54.

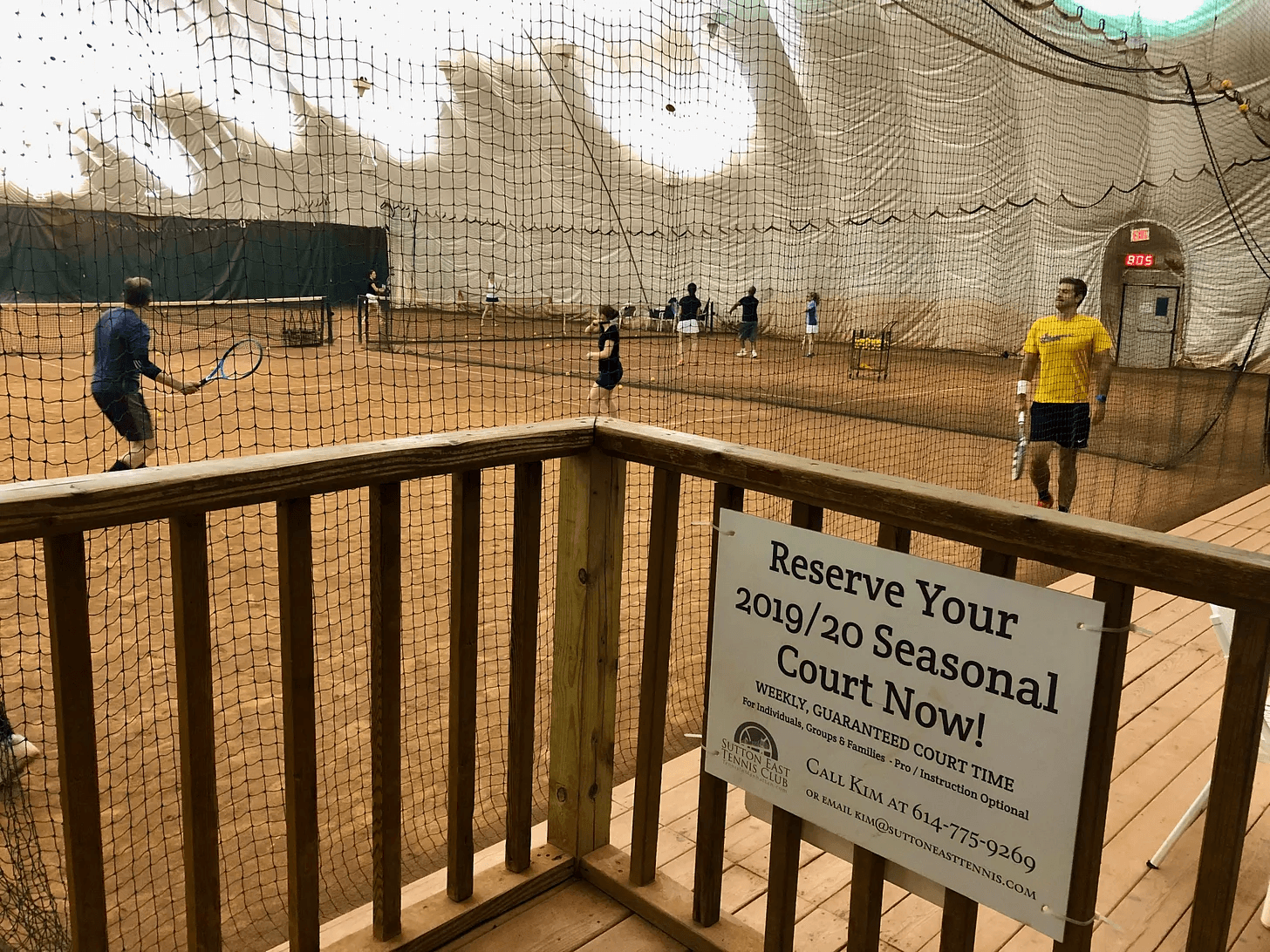

The indoor bubble at Sutton East Tennis Club. Built on park grounds, the group that runs the club now allows reduced rates for Seasonal Park Pass holders.

Sutton East Tennis Club

In mid-2017, the populists of the Upper East Side finally won a battle against the elitists. A spot of rich, red clay courts formerly known as the Queensboro Oval tennis bubble — operated by a group calling itself Tennis in Manhattan through a license agreement with the city — opened to city tennis permit holders, following a rancorous grassroots battle cry. East Siders wanted a multi-sports venue with an ice-skating rink in the winter, but the one-acre tennis facility, under the Queensboro Bridge on the Manhattan side — which once hosted softball players in the summer, tennis players in winter — went all-season on June 16, 2017, handing over six of the club’s eight courts to city tennis permits at no extra cost. Normally, the club charges from $80 to $225 per court per hour during peak off-season times.

The lounge at Sutton East Tennis Club. Half-indoor, half patio, it’s one of the most unusual waiting areas in Manhattan.

Tony Scolnick, the proprietor of Tennis in Manhattan, which runs the Vanderbilt Club at Grand Central Station as well as the Yorkville Tennis Club, opened Sutton East in 1979. He currently pays a $2 million per year lease on the land to the city. When the neighborhood ballplayers gathered 1,000 signatures to convert the grounds back to a city park, Scolnick, a former Athletic Director for Hunter College and player at Springfield College in Massachusetts, fought back with 3,000 signatures from users of Sutton East. “People will be thrilled because when it rains in the summer they can't play outdoors,” he told the former news site DNA.info in 2017. “We believe thousands of people who play at our facility, if they don't have a permit, will go and get one. We are very happy to maintain the courts.”

An after-school program of New York Junior Tennis and Learning (NYJTL), which has the courts weekday afternoons. Evenings and weekends, courts cost a pittance.

The Harlem Armory

Located at the Armory building at 143rd Street and Fifth Avenue — the former home of the 369th Regiment “Harlem Hell Fighters” — the Harlem Armory Tennis Center runs eight indoor courts on the medieval-inspired drill shed built in 1921 for once training the New York’s first black National Guard regiment. After the war, Nick's Indoor Tennis took over the facility, followed by Bill's Indoor Tennis, which then became the Harlem Tennis Center (HTC). During the afternoons, the Harlem Junior Tennis and Education Program (HJTEP), runs programs for local children. But during mornings, nights and weekends, courts are available at below-market rates.

Graffiti portraits of some of the great Black tennis players of the modern era line the stairs leading up to the court-office at the Harlem Armory Tennis Center.

The armory, which also has a nice art-deco wing, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1994. Tennis greats Arthur Ashe and Althea Gibson played at the Armory before getting involved in junior tennis — Gibson in Newark and Ashe with the New York Junior Tennis and Learning (NYJTL) program. Under the city bankruptcy tenure of Mayor Ed Koch, half of the courts were used as homeless shelter, but Mayor David Dinkins — an avid tennis lover and player — turned over the courts to HJTEP in the early 1990s.

The courts at the Frederick Johnson playground light up around 6pm every day, even in the winter.

Frederick Johnson Park

Possibly one of the least-known tennis jewels of Manhattan, the recently restored Frederick Johnson Playground offers eight courts in Harlem, open from April through November — with lights! Once affectionately known as “the Jungle”, according to the Times, these courts were also once a mecca for top African-American players. Frederick Johnson, the park’s namesake, coached Althea Gibson there — with one arm.

A monument to the Park’s namesake, who coached Althea Gibson as a young girl.

In 2010, former mayor and tennis enthusiast, David Dinkins, helped form the David Dinkins Tennis Club — a free family program on summer weekends. Dinkins was also instrumental in installing lights at Frederick Johnson when he served as Manhattan borough president in 1986. But other than that programming, the city has maintained a mostly hands-off approach to the small slice of New York tennis utopia tucked into a corner of northeast Manhattan.

Adrian Brune

Content